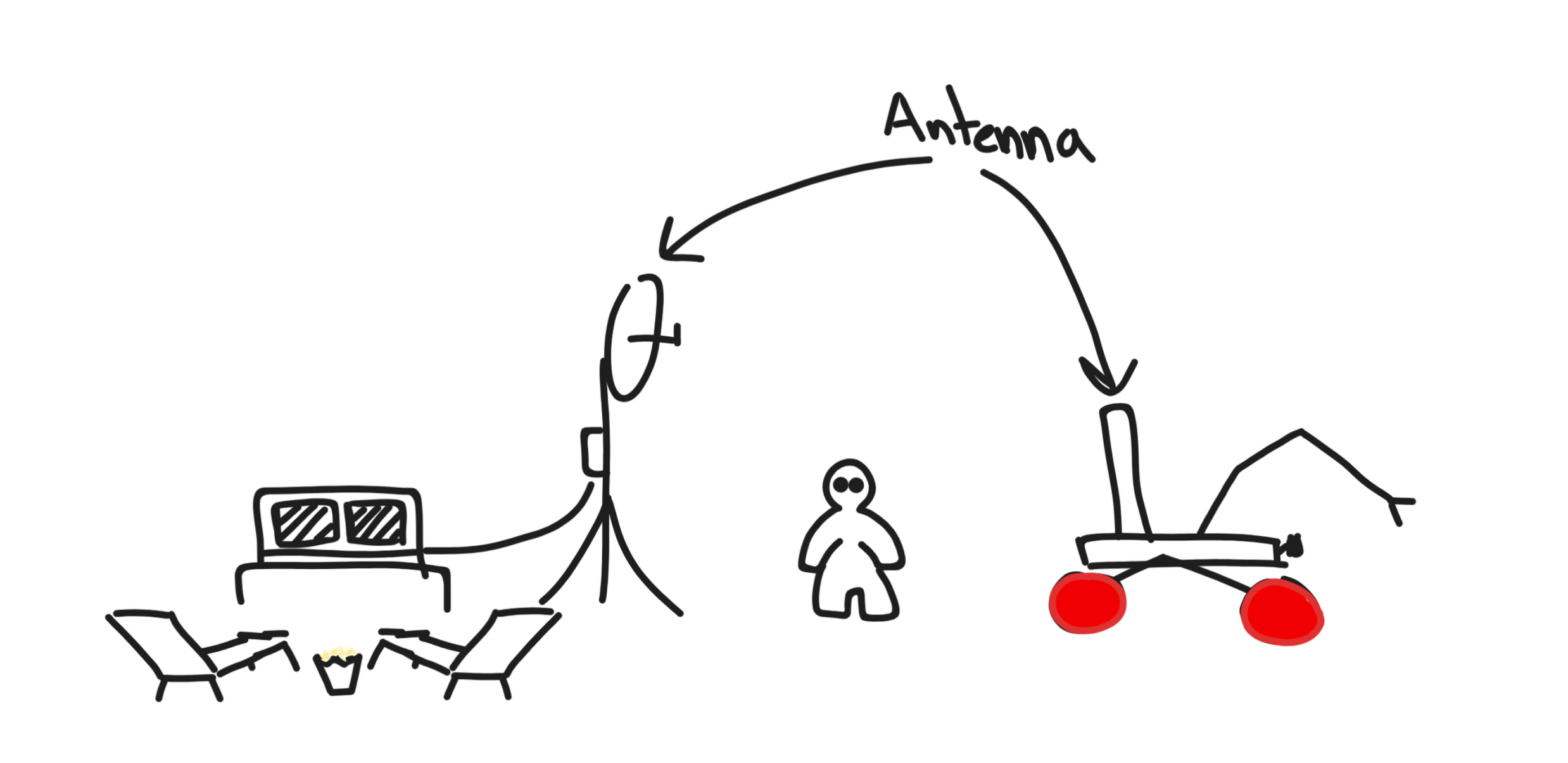

For a second imagine (I know it might be hard, you’ve got this) that you are on an epic mission to survey the mountain ranges of Mars. This is a dangerous mission, so you send your trusty rover named Spike to safely stare at rocks and take cute selfies up and over these mountain ranges.

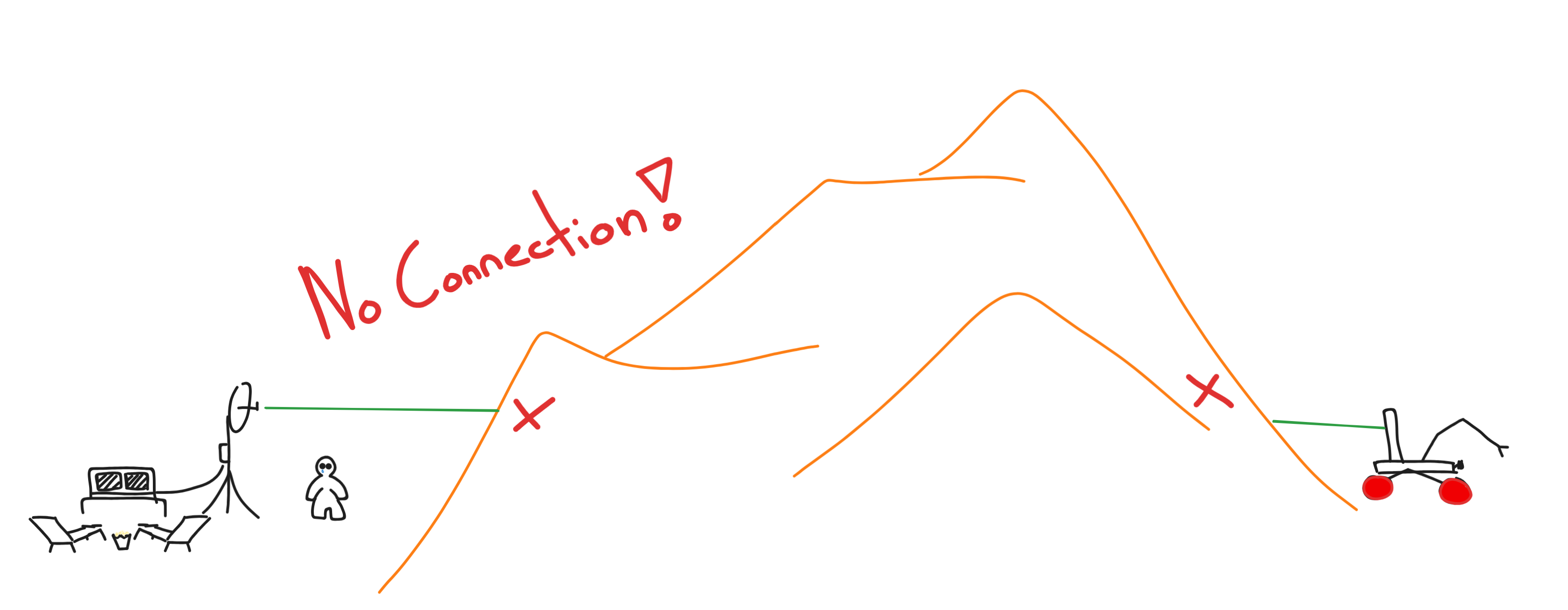

There’s an issue though, we can’t enjoy our mountain movie if our antennas cannot talk to each other. This can certainly happen when our rover is out of range, or more specifically, not in line of sight. When we leave line of site our radio waves tend not to be able to travel very well through the rough martian terrain, so we need to figure out how to extend our range.

There’s an issue though, we can’t enjoy our mountain movie if our antennas cannot talk to each other. This can certainly happen when our rover is out of range, or more specifically, not in line of sight. When we leave line of site our radio waves tend not to be able to travel very well through the rough martian terrain, so we need to figure out how to extend our range.

The problem is glaringly simple, but it’s not an easy one to solve

The problem is glaringly simple, but it’s not an easy one to solve

in essence,

::: problem How do we maintain a connection in NLOS operating conditions? :::

This is exactly the kind of problem our design team and many other teams like ours face year to year at competitions like URC in Hanksville, Utah and CIRC in Drumheller, Alberta.

The competition format has historically always had a traversal mission where we must drive the rover to a location either provided to us by coordinates or must be navigated to by markers place along the route.

At this point I hope you would’ve thought, “why don’t you just choose a route that always has line of sight?“. And that is a great thought, but these competitions would not have the word “challenge” in them if they did not make it challenging. Both URC and CIRC make it so its almost guaranteed that you’ll have no line of sight with the rover at critical portions in the traversal mission. I say almost, because there are still some cheeky ways you can get line of sight… but that will come later.

The Bad Ideas

The more problems I have solved (or tried to at least) the more I have realised how easy it is to come up with bad ideas. These bad ideas may seem, well, bad in the moment but they pave an excellent route to an acceptable solution. That being said, here are some of the bad ideas the team and I had thought of.

Bad Idea 1: Hopes and Dreams

While being a great thing for your mental health and dreaming certainly drives innovation, this strategy won’t get you far in a rover competition. No matter how hard you manifest for those radio frequencies to travel through a couple meters of Utah stone it won’t happen. But you may certainly dream of a better solution!

Bad Idea 2: Tuning Antennas and Adding Power

Hmm this one sounds a bit more realistic. But of course as a computer science major I believe “anything can be fixed if we optimise it enough”! But this is almost never the answer. Regardless there are a lot of parameters we can play with the get optimal throughput.

Bad Idea 3: A Fuckin Balloon

…

Bad Idea Good idea 1: Deployable Relay

Aside from being able to name this option D.A.F.A.R.T. (Deployable Asynchronous Fucking Awesome Receiver and Transmitter) it is actually a viable option. The concept is simple, drop a relay to get rid of dead zones where the rover is expected to go.

So we build a lil box with antennas on it, strap it to the rover (or even the drone) and drop it in an optimal location. Done?

I wish, this shit is way more complicated. But nothing to be discouraged by. Lets layout the setup first and play I-Spy to find what is wrong.

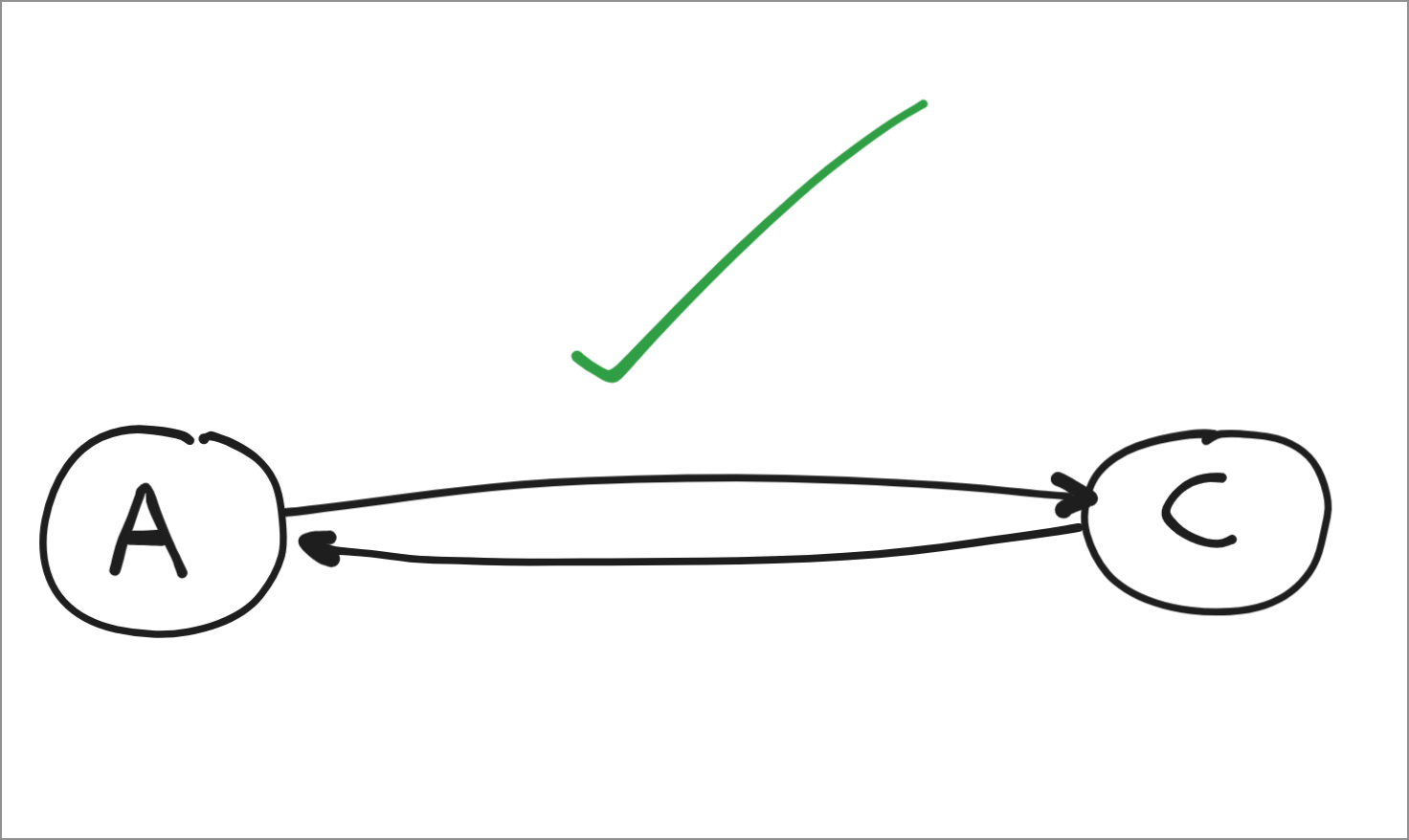

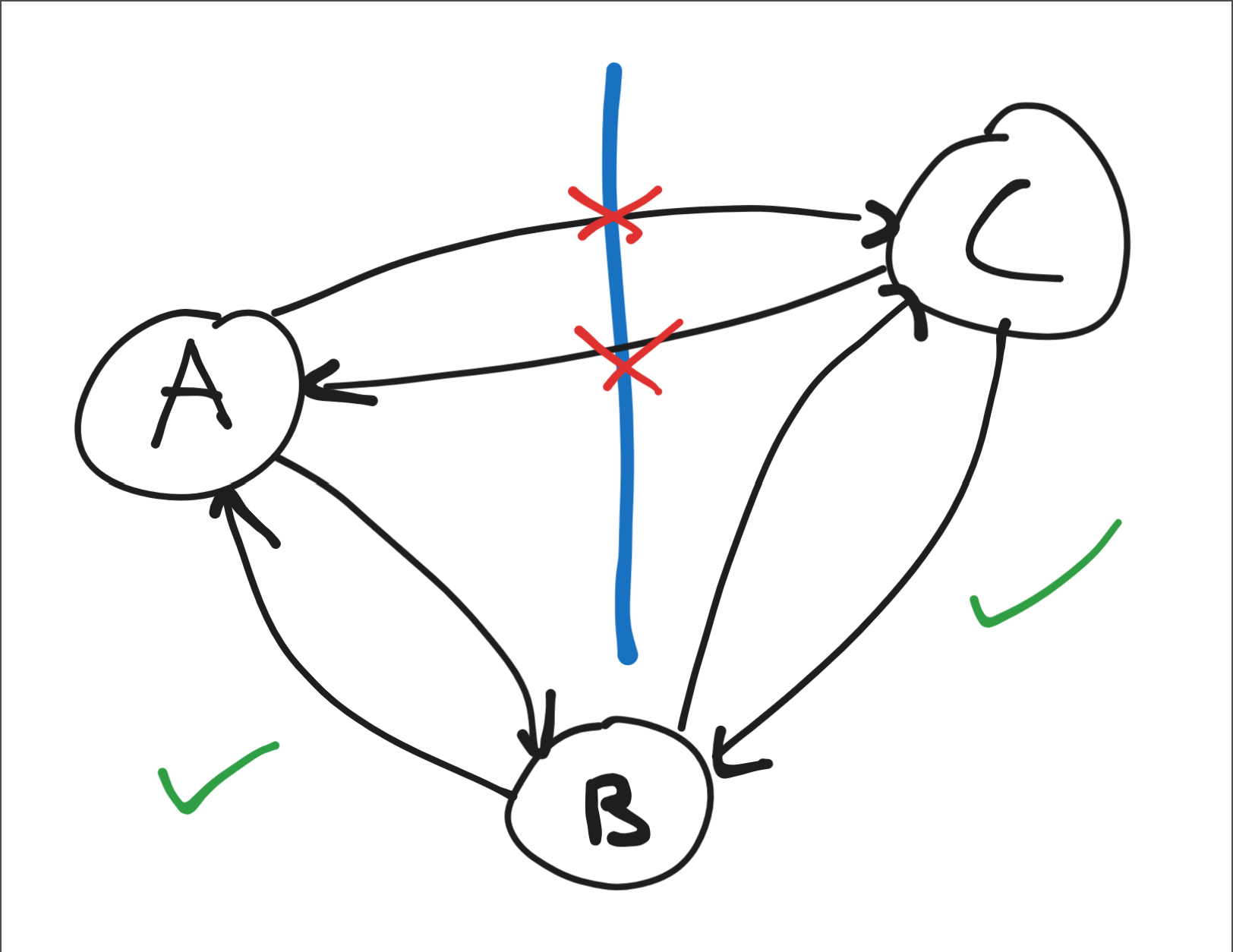

In the most trivial configuration we have two happy nodes A (the base station) and C (the rover). We have perfect line of sight, no obstructions, everyone is happy, data is flying over the air.

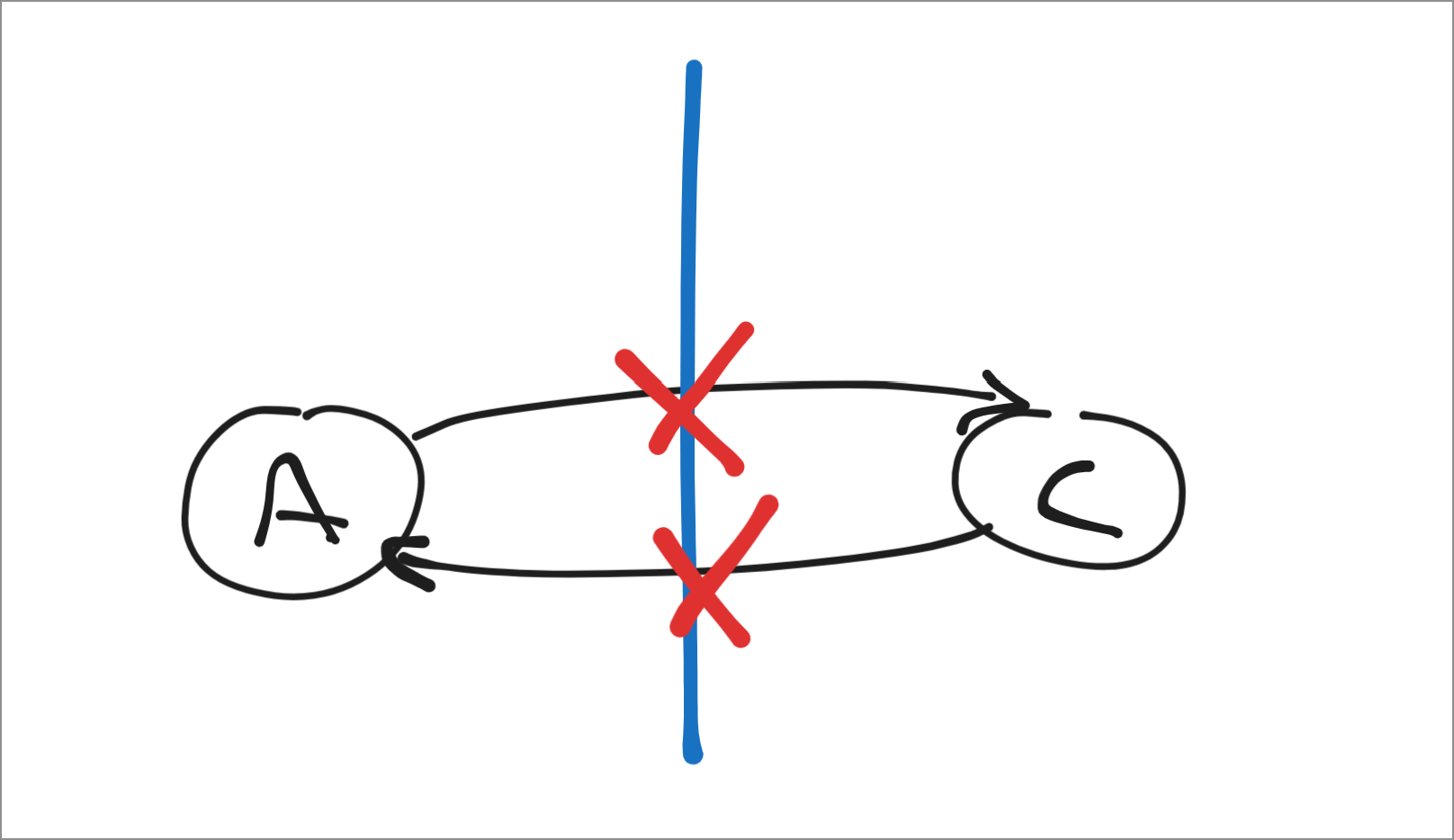

But life is miserable and like Buddhism tells us, life is suffering. We have lost all line of sight, there no possibility of getting our data through this obstruction (realistically at least). But what if…

But life is miserable and like Buddhism tells us, life is suffering. We have lost all line of sight, there no possibility of getting our data through this obstruction (realistically at least). But what if…

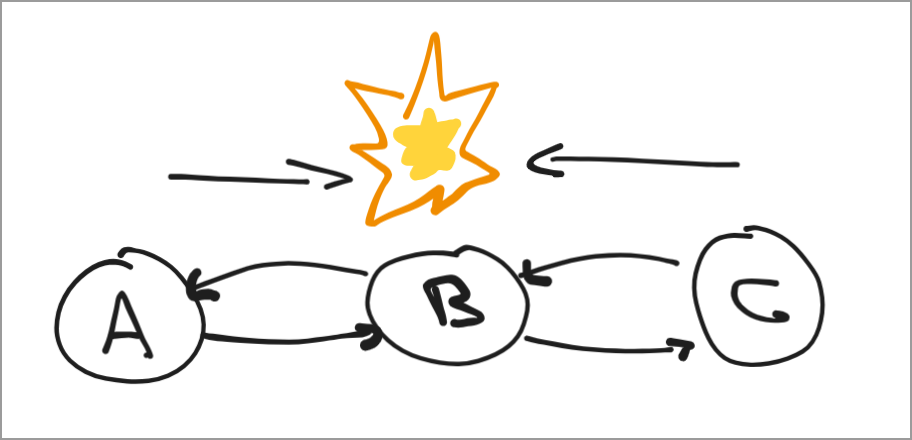

we added a intermidate relay node (B) to relay any messages it catches from the rover back to the base station! Alright, job done, our obstructions have been navigated with careful relay placement and a smart routing syst…

we added a intermidate relay node (B) to relay any messages it catches from the rover back to the base station! Alright, job done, our obstructions have been navigated with careful relay placement and a smart routing syst…

Fuckkkkk. So there’s a limitation to what we can do reliably due to this system having a hidden node. Node A is aware of B and it’s timing of messages, C is aware of A’s existence, and B of course knows about both A and C. But the problem is that A is not aware of C and vice versa. This means that both A and C might try to send signals to B simultaneously leading to race conditions, dropping entire packets. This is the hidden node problem, and is something that is difficult to solve efficiently simply with software. One such way is through TDMA (time division multiple access) which is a mechanism in which each node is assigned a schedule of when it can send and cannot send. This ensures that A and C never send B data at the same time. Unfortunately this is not an option for us to implement on the existing system (yet…) .

Fuckkkkk. So there’s a limitation to what we can do reliably due to this system having a hidden node. Node A is aware of B and it’s timing of messages, C is aware of A’s existence, and B of course knows about both A and C. But the problem is that A is not aware of C and vice versa. This means that both A and C might try to send signals to B simultaneously leading to race conditions, dropping entire packets. This is the hidden node problem, and is something that is difficult to solve efficiently simply with software. One such way is through TDMA (time division multiple access) which is a mechanism in which each node is assigned a schedule of when it can send and cannot send. This ensures that A and C never send B data at the same time. Unfortunately this is not an option for us to implement on the existing system (yet…) .

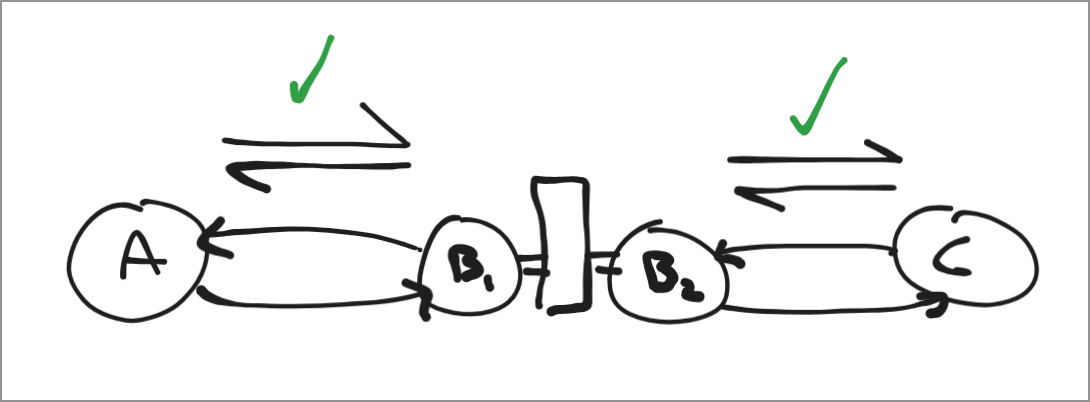

To solve this hidden node problem we simply set up two radios on the relay, both dedicated to receiving (and transmitting) from only one each. By still being able to capture from both sides we can simply buffer the packets on our controller driving the radios and process two streams asynchronously. This does come at a few challenges where we need to source a device with slots for 2 radios (or two built in), and buy 2 radios, and 2 antennas for the one relay. So a little more expensive, and a little more complex, but way more robust, which for mission critical features like communication is vital.

To solve this hidden node problem we simply set up two radios on the relay, both dedicated to receiving (and transmitting) from only one each. By still being able to capture from both sides we can simply buffer the packets on our controller driving the radios and process two streams asynchronously. This does come at a few challenges where we need to source a device with slots for 2 radios (or two built in), and buy 2 radios, and 2 antennas for the one relay. So a little more expensive, and a little more complex, but way more robust, which for mission critical features like communication is vital.

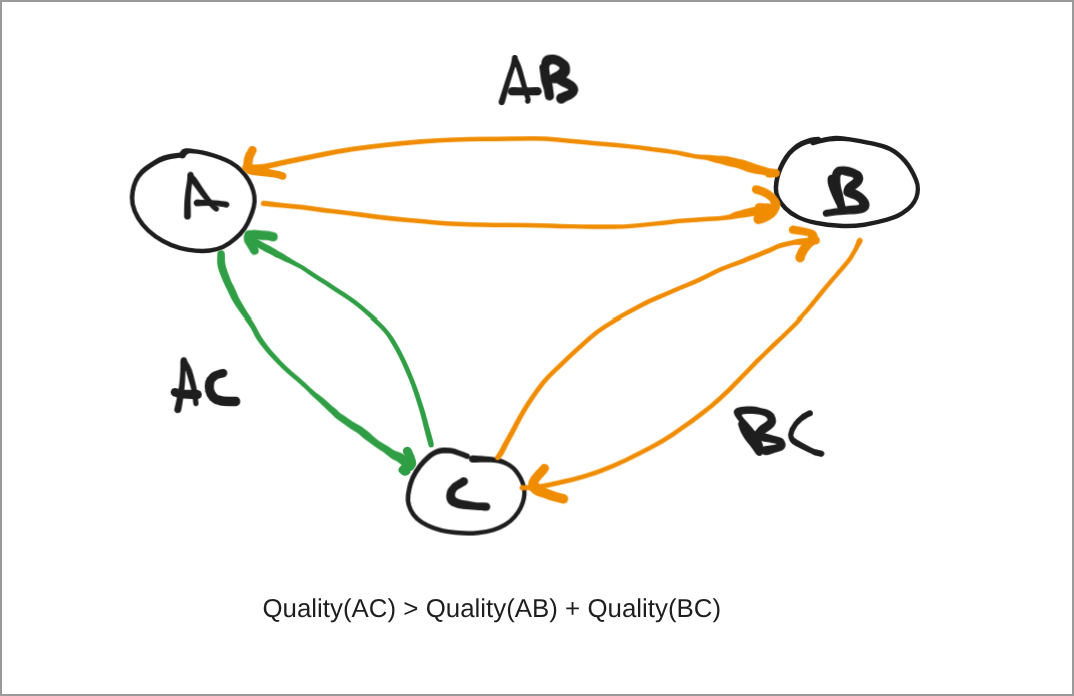

Lastly less of a critical problem but what do we do when we are done with our relay and have line of sight back with the base station? Surely we do not want to run our connection through our relay. So our relay implementation must have some meshing capabilities, to prioritise traffic based on link quality.

After doing some google searching a gem fell upon me, the exact piece of software I need to solve all (I wish) my problems. Its called BATMAN-Adv, a kernel module that creates and manages a mesh at Layer 2 of the network stack. That means its almost transparent to us in terms of networking, it just manages routing and passes us the unadulterated packet to pass upwards to our application. By setting up all three nodes rocking a routing software like OpenWRT with BATMAN-Adv. we can setup a mesh robust enough to handle our NLOS conditions. And it would be a good base to work from if we decided to expand our mesh.

Lucky for me, our team got donated these sweet radio packages, that were probably meant for meshing, I intend to capitalise the opportunity.

Salvaging a Relic

Not too long ago my design team received a donation of 3 x RAJANT Gateways which in their prime were most probably used to create a mesh network on a construction site, or maybe on military vehicles (who knows…). Regardless, I wanted to know what was in these gateways, as if they have the right hardware we could easily use these as a proof of concept for a deployable relay allowing for a simple and robust 3 node mesh network.

The main goal I have is to see if these guys can run OpenWRT. If they have support we can load BATMAN-Adv a kernal module that enables meshing by controlling the layer 2 interfaces (in this case the WiFi cards)

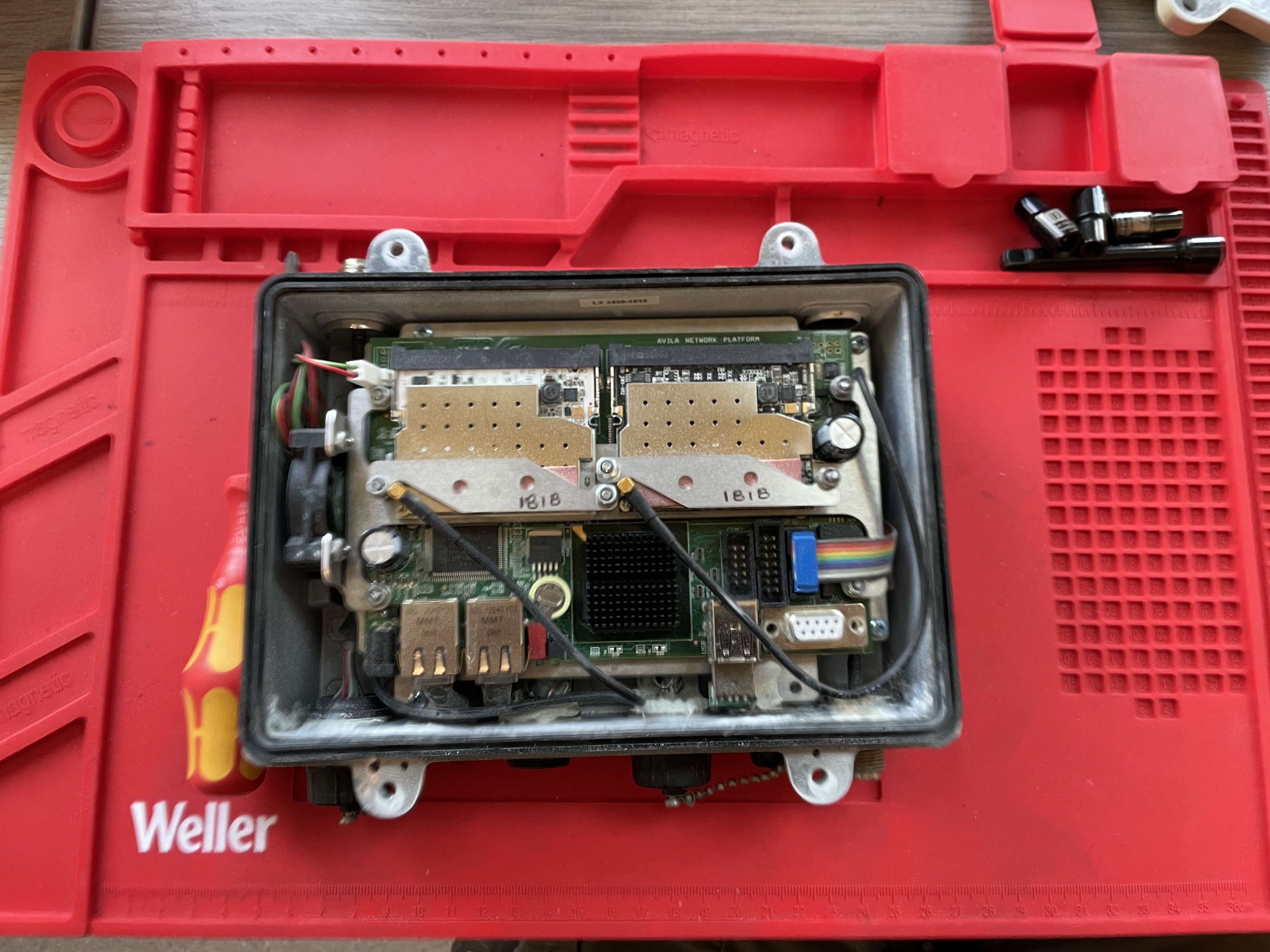

Taking off the cover leaves us with this compact board. We can see some exposed interfaces giving us some hints on how we may interface with this guy. Immediately I notice the 2 distinct WiFi cards, and the fact that they are interfacing with the rest of the board via mini-PCI! We can also see the exposed RS485 female plug, I presume this gives us access to a serial terminal… Some other interfaces include JTAG headers, and where you see the blue cable is attached is some GPIO.

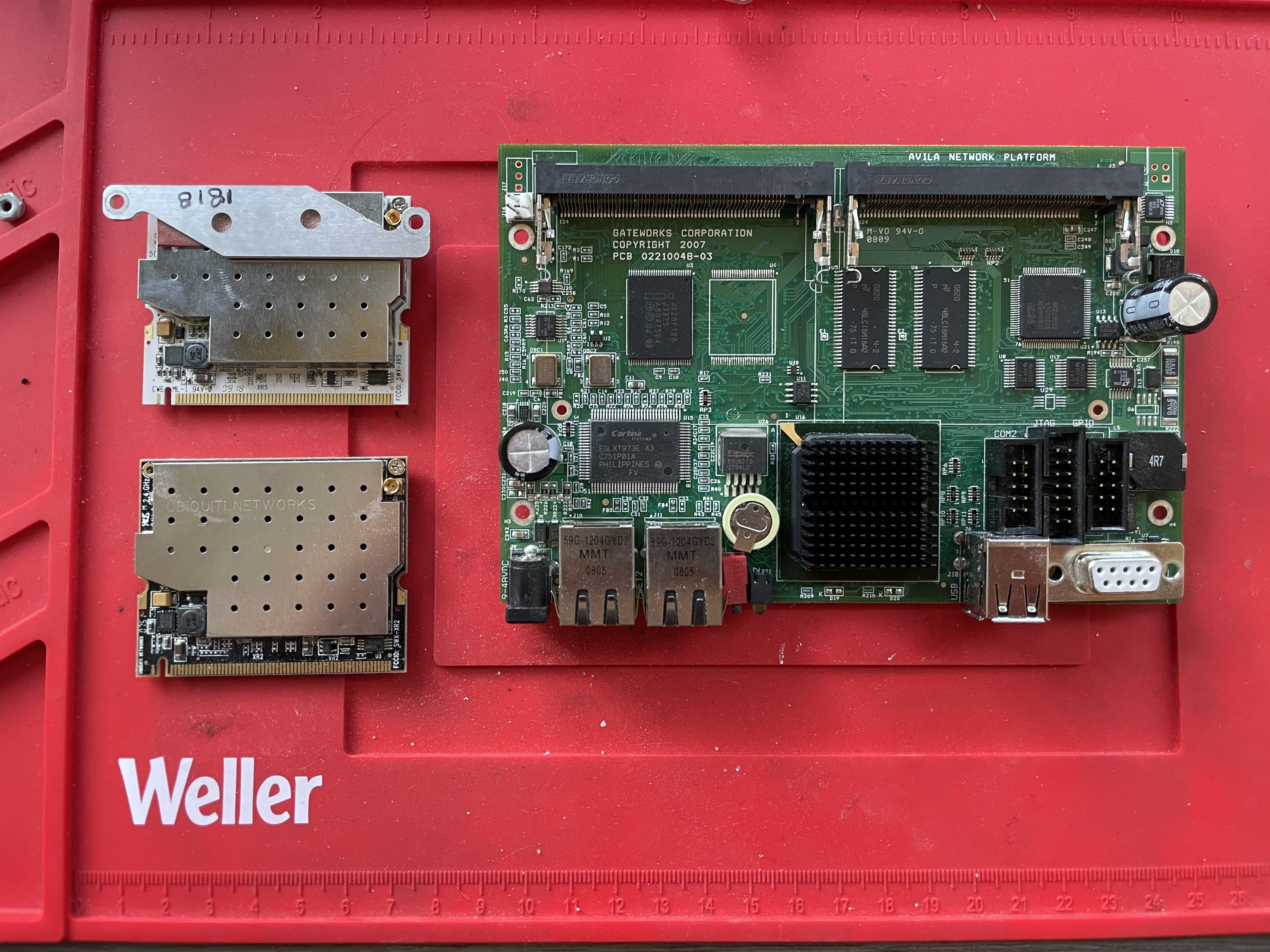

Taking it apart further with the mini-PCI cards removed, and all the custom supports removed we are left with this!

Taking it apart further with the mini-PCI cards removed, and all the custom supports removed we are left with this!

This was quite cool to me because now we can clearly see what the hardware is! Inspecting it closer we see this is pretty much a single board computer. Its a platform that was once produced (or designed? Im still unsure) by a company called Gateworks. This computer they call the ‘Avila Network Computer’. Now finding the documentation for this guy was not super easy, as I find out that it is roughly as old as I am, so the relevant documents are a bit buried. But after digging it up we get a nice spec sheet, and DAMN for today’s standards that CPU is slow as balls.

This was quite cool to me because now we can clearly see what the hardware is! Inspecting it closer we see this is pretty much a single board computer. Its a platform that was once produced (or designed? Im still unsure) by a company called Gateworks. This computer they call the ‘Avila Network Computer’. Now finding the documentation for this guy was not super easy, as I find out that it is roughly as old as I am, so the relevant documents are a bit buried. But after digging it up we get a nice spec sheet, and DAMN for today’s standards that CPU is slow as balls.

Out of curiosity I dug into what processor is running on this artefact. The board know by model GW2342, is rocking an absolute unit of a networking CPU called an Intel XScale IXP425. This CPU was a workhorse back in its day presenting with a very interesting architecture. Ill talk about it a little bit here, but if you want to skip be my guest.

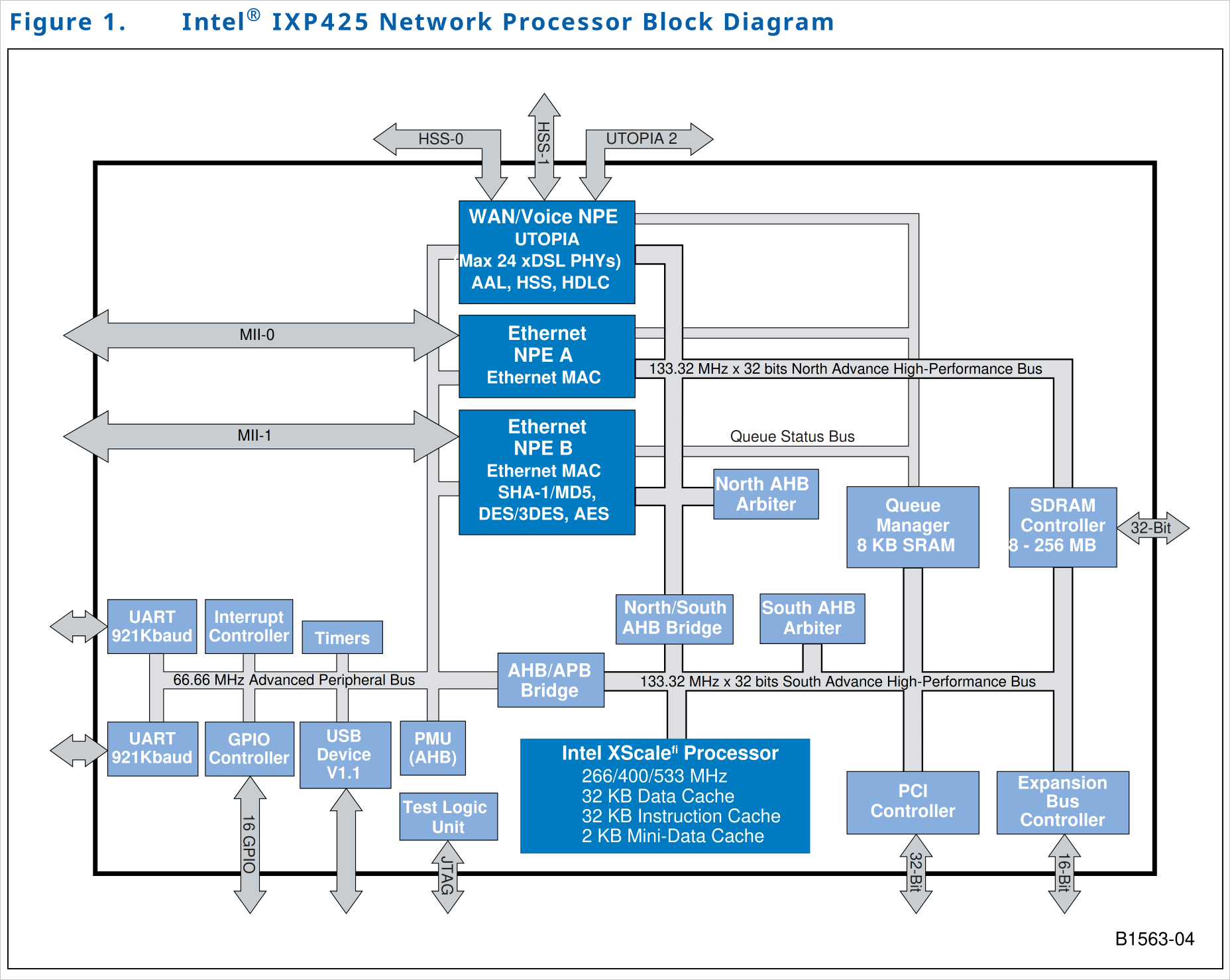

The Intel XScale IXP425 Processor

As most modern processors do, the SoC contains pretty standard peripheral busses, a PCI controller (not to be mistaken with PCI-e). But intrestegly it has a special UTOPIA network processor. UTOPIA is actual a standard interface called Universal Test and Operation PHY Interface for ATM. It defines a full-duplex bus with seperate data and control lines for networks that use the ATM (Async Transfer Mode) standard. It enabled connecting ATM based network equipment. For example you could hook up multiple DSPs on one bus in a way that they will understand each other using ATM. In the case of our gateway product, this feature was not used. With this bus we could have a DSP connecting as a coprocessor to perform extra tasks to offload from the main processor and NPEs (network processing engines). The network processing engines have the capability to do AES and the now defunct MD5.

As most modern processors do, the SoC contains pretty standard peripheral busses, a PCI controller (not to be mistaken with PCI-e). But intrestegly it has a special UTOPIA network processor. UTOPIA is actual a standard interface called Universal Test and Operation PHY Interface for ATM. It defines a full-duplex bus with seperate data and control lines for networks that use the ATM (Async Transfer Mode) standard. It enabled connecting ATM based network equipment. For example you could hook up multiple DSPs on one bus in a way that they will understand each other using ATM. In the case of our gateway product, this feature was not used. With this bus we could have a DSP connecting as a coprocessor to perform extra tasks to offload from the main processor and NPEs (network processing engines). The network processing engines have the capability to do AES and the now defunct MD5.

Exploring more toward the actually XScale core, we see it has a “super pipeline” with 7/8 stages,

a super pipeline just describes a pipeline that has a deep pipeline with many stages. Originally I thought super pipelined meant it is somehow also super scalar, but that is NOT the case. It is still a simple single-issue in order execution mechanism.

Integer Pipe

- Fetch 1

- Fetch 2

- Decode

- Register File

- ALU Exec

- State Exec

- Integer write back

Memory Pipe

- Fetch 1

- Fetch 2

- Decode

- Register File

- DCache 1

- DCache 2

- DCache write back

MAC (Multiply-Accumulate) Pipe

- Fetch 1

- Fetch 2

- Decode

- Register File

- MAC 1

- MAC 2

- MAC 3

- MAC 4

- DCache Write Back

and no sight of an FPU!. If you think about it when in networking do you encounter floating point numbers? Almost nowhere! It all surrounds integer math. Most of it is table lookups for routing, MAC addresses and ACLs. Or packet header manipulation. Everything there is of a fixed size. Pretty convenient.

On the more interesting side of things reading the description of the core processor, it says that

“The Intel XScale technology is compliant with the ARM* Version 5TE instruction-set architecture (ISA).”

I never knew intel every worked with ARM ISA’s! Looking at the history it seems Intel had bought Digital Equipment Corporation in 1997 which came with the ownership of StrongARM an ARM implementation. Intel maintained it before evolving it to XScale. This was Intel’s only ever ARM implementation (technically). Then XScale was sold to Marvell in 2006, and Intel has never made a ARM implementation. But recently intel has been manufacturing ARM chips using Intel processes at the foundry in a cool deal between ARM and Intel. Additionally it supports ARM 5TE instruction decoding which is an extension for DSP operations.

This means our little processor represents an interesting era for Intel continuing to prove itself as THE industry leader of its time That’s pretty fucking cool in my opinion.

Most importantly this XScale processor is supported to run OpenWRT a popular and flexible router operating system based on Linux. The foreshadowing is that I intend to use OpenWRT on this mother(board)-fucker.

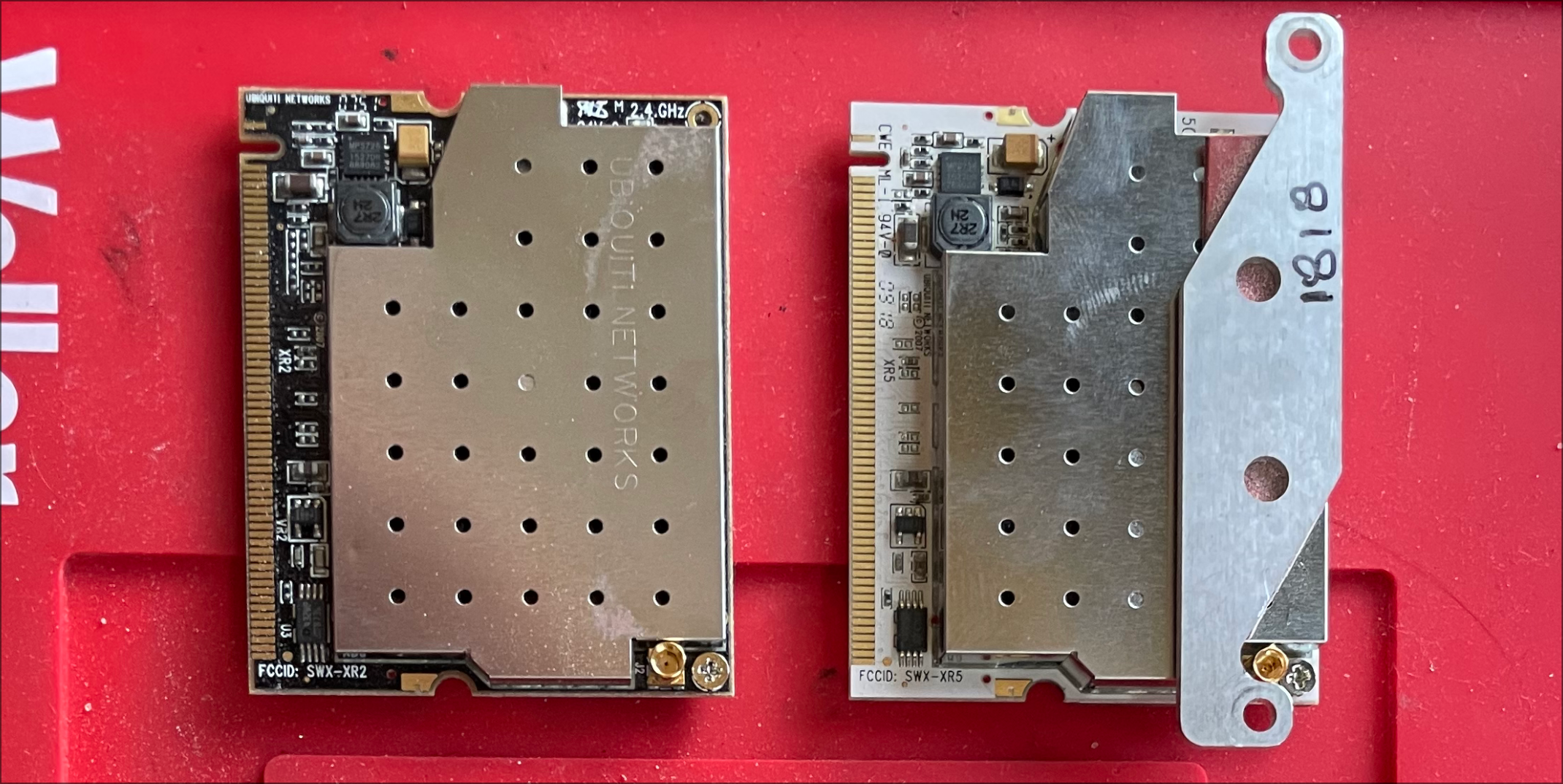

The WiFi Cards

These also have an interesting story. Today I found out that Ubiquity used to make expansion cards. These two lil dudes are wireless cards that operate on the 802.11g standard which like a lot of these components is older than me. The two cards are the (from left to right):

These also have an interesting story. Today I found out that Ubiquity used to make expansion cards. These two lil dudes are wireless cards that operate on the 802.11g standard which like a lot of these components is older than me. The two cards are the (from left to right):

- XR2 by Ubiquiti Networks a 2.4Ghz radio running at 600mW

- XR5 by Uiquiti Networks a 5Ghz radio also running at 600mW

Surprisingly still sold by Ubiquity Networks.

Also thankfully these modules are ran by the Atheros AR5414 chipset which has drivers for OpenWRT!

Firmware

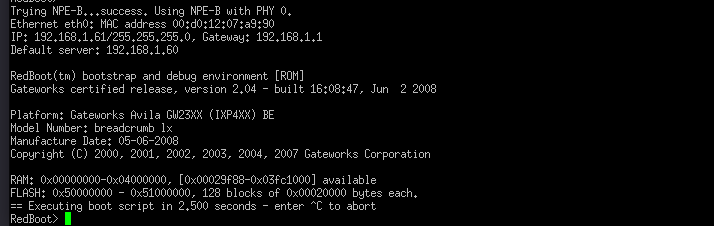

Helping to perform updates and load kernels is the RedBoot boot loader. This bootloader is a little special because it contains a super small file and simple transfer protocol implementation called the Trivial File Transfer Protocol, which is small enough to fit in a bootloader to drive updates over network interfaces. TFTP

TFTP is not used anywhere anymore…

I did not want to deal with setting up networking to access a shell so I decided to connect over the RS232 port to get serial shell access to the board. This took me ages to do because I needed to put together a RS232 harness and my solder skills are shoddy. In the end I used the serial port from the ol’ build machine that we have setup in the design team’s workspace. Worked without any issues.

Using a serial monitor like PuTTy we connect to at 115200 baud (a lucky guess) and press the reset button on the board and we get bootloader, oh yeahhhhhh!

Using a serial monitor like PuTTy we connect to at 115200 baud (a lucky guess) and press the reset button on the board and we get bootloader, oh yeahhhhhh!

Having worked with scripts to load firmware and custom tooling for firmware loading, loading binaries on this guy seemed way too easy. I just slapped an Ethernet cable between the SBC and my PC and started a TFTP server on the PC. I just had to call

Having worked with scripts to load firmware and custom tooling for firmware loading, loading binaries on this guy seemed way too easy. I just slapped an Ethernet cable between the SBC and my PC and started a TFTP server on the PC. I just had to call load with the IP of the PC, the name of the binary and where in RAM (or Flash) I want to load the binary.

Lets see if we can get Linux, or specifically OpenWRT to run on this board.

No Space!?

Here’s the first challenge with the firmware, and its more of a limitation placed by the hardware. This board has so little RAM and Flash that there is no way it would fit a modern OpenWRT implementation. Even though modern OpenWRT does support older chipsets like the XScale processors, it does depend on how much space these devices have.

OpenWRT 24.10 a recent release takes up 2.9 Megabytes for the kernal and another 3.3 Megabyte for the root file system,